Probably the most common question prospective humanities majors ask is “What good is a humanities degree? I really enjoy what I am studying, but I need to be concerned about getting a job. What can I do with a humanities degree?”

This question looks like one question, but it really disguises several related ones. Distinguishing them will allow us to answer each of them more clearly.

1. Will humanities help me think of a good career? I don’t know what I want to do yet, and I don’t know how to find out.

For many people, this is what they really mean when they want to know whether a humanities degree will lead to a job. The fact is that there are a lot of careers out there, and most undergraduates don’t have enough experience in the world to know what the options are. Our ideas about possible careers are informed by what people we know do and what we see on television. That’s not a very large sample set.

What’s needed is experience. And there are ways that you can get that while you are in school. Find internships, service learning, co-operative learning, or volunteer opportunities. Travel. Work somewhere other than your home town in the summer. Talk to people you know who seem to like their jobs, and ask them what they like about them (people usually like to talk about themselves and what they love, if you catch them at the right moment). And keep your eyes open.

You can go to one of the big career websites and see what’s listed there, but those listings don’t really tell you much about what it means to be in the career. It’s better to just start experiencing the world. You can probably do that with the help of your university. UCF has a coop/experiential learning department, as well as an international studies office.

But there’s another aspect of this that you should keep in mind. What you really are asking is about whether the humanities will help you identify a vocation. We sometimes talk about careers as “vocations”, which in the Latin root (vocatio) literally refer to a calling, a summons, or an invitation (think of other English words that use the same root – e.g., vocalize, invoke, evoke – all terms that are about bringing something into reality through words). “Vocation” is often used in religious circles – people are called to be clergy. But the term really refers to the connection between life and action, between who you are and what you do. To have a vocation is to do the thing that makes you the best of what you can be. A real career is a vocation – you know you’re in the right place, doing the right thing for yourself.

There’s another related Latin term, vocamen, which means “to have a name” (or “to be called something”). A vocation is like having a name. It means that you can say, for instance, “I am a writer”, rather than just, “I have a job writing” or “My job involves writing”. If you have a vocation, your job becomes an extension and expression of who you are. It means that you are doing something that truly exercises your skills, and something in which you can say at the end of the day, I’ve made a difference today.

Isn’t that what we all really want, to do something that integrates our thoughts, desires, and actions? Isn’t that what it means to have integrity, to have all parts of your life in sync? It’s worth noting that, in order to get to this vocation, you need to know yourself. A lot of people think that this just comes naturally, but it doesn’t. This is ultimately what the humanities do the best. It is, after all, what the Delphic Oracle meant with the inscription “Know Yourself”, what Socrates meant when he said that the unexamined life is not worth living, and what Kant meant when he summarized enlightenment in the phrase Sapere Aude! – “Have courage to use your own reason”. Of course, this isn’t going to be completed in your humanities degree – knowing yourself is a lifelong task, more of a journey than an achievement. But this is a great place to start.

Now, a job might be an aspect of a vocation, and it might not. Vocations are often made up of jobs, but jobs don’t necessarily make a vocation (and indeed, some peoples’ vocations don’t involve a job at all). Most people want a good job, one that pays lots of money. Money is fine, but it’s a means to an end (see below for more on this). You still need to figure out what that end is.

2. I have a good idea of the career I want, but I’m concerned about whether humanities will prepare me for it.

You’re actually in a good position. What I just said about vocation and integrity is still true for you, but you might already have an idea of how to integrate yourself with your desires and actions. If you know the kind of career you want, you can start to identify the skills that the most successful people in the field have. The earlier you identify those, the earlier you can start deliberately working on those skills yourself.

Find a mentor, if you can – someone in the field who can tell you what it takes to succeed, and who would let you tag along sometimes. Then, start deliberately cultivating the skills that are needed. Take some courses that will develop those skills. Find a minor (or double major) that will help further with that. In your classes, you might have an opportunity to write a paper on some issue in that field – take that opportunity. You will develop your skills, and you will also have tangible evidence of your interest when it comes time to look for a job.

Will humanities prepare you for your desired career? Obviously, it depends on what that career is. In some cases it will, and in some cases a career requires very specific educational qualifications. One thing is certain, though – a humanities degree will make your chosen career better. It will enable you to succeed in your career, as well as helping you to get your first job. It will enable you to advance in any career, because you’ll have the writing, speaking, and thinking abilities to do so. That’s why a double major is often a great option, with a humanities program as part of that mix.

3. Can I really study what I want to, and still earn a living at the end of it?

That’s the real question for many people. The humanities have the virtue of being amazingly interesting, because they deal with what it means to be human in all its complexity and wonder. It’s hard to resist that, which is why we tend to get students who are passionate about their life and their studies. But we have this idea that doing what is good for us must be boring, and doing what’s interesting must not be productive.

In fact, the opposite is true. If you truly enjoy your studies, you will find your own way to bring it to life, and to make it your life. Do you really want a disconnected life, one in which you have a career you don’t really like but which makes money, so that you can enjoy your life on the weekends? Ideally, we all want an integrated life. Your goal should be to find a way to do what you love, and make your education support that. That’s what a real vocation is.

So, the question is not, how do I make a lot of money, but rather, what does living well mean for me? We need to support ourselves, obviously, and we all want to have money, but money is just paper if it doesn’t lead to a good life. Money is not the way of scoring life to determine who wins. Some people think that money all by itself will lead to good things, and others think it’s our major means of measuring success and significance. Neither are really true – there are plenty of stories of wealthy, unhappy people, and even winning the lottery does not guarantee a greater degree of happiness than not winning the lottery. As long as we think of of money as an end and not the means to an end, we are not in control of our own lives. It is better to know who you are and be able to use all the resources at your disposal to the end that you truly desire, than to let those resources control you. Being truly free (which is, after all, the point of the “liberal” arts, or the habits and disciplines of the free person) means choosing your own self, and then figuring out what it takes to bring that self into reality.

Does all this mean that we don’t think you can make good money with a humanities degree? Not at all. In fact, many extremely wealthy and famous people started with degrees in humanities disciplines. There are CEOs of major corporations who started with humanities degrees. There are actors, directors, artists, musicians, and sports figures who started with humanities degrees. Look amongst the ranks of doctors, judges, presidents, humanitarians, environmentalists, scientists, business leaders, broadcasters, diplomats, social activists – you will find humanities degrees. The point is that you need to first think about who you are and what makes sense for you, and second, how you can turn that into a successful vocation.

4. Are there jobs out there that ask for humanities graduates?

Of course, you need something concrete when you get out of university. All this talk about careers and vocations may be fine, but there are student loans to pay and nice things to buy. Will your humanities degree lead directly to your first job?

Well, the first thing that should be said is that, yes, employers do look for humanities graduates. Look at “In a New Generation of College Students, Many Opt for the Life Examined” (New York Times, April 6, 2008), and “I Think, Therefore I Earn” (Guardian, Nov. 20, 2007) for evidence of that. Tony Aumann‘s page at Northern Michigan University has more links to articles on the value of the humanities, especially philosophy.

If you’re looking for a job that says in the job ad “humanities degree preferred”, you won’t find many of those. That doesn’t mean that your degree doesn’t lead to a job, though. You have to think in terms of marketing the skills you have developed. You have to translate your skills for an employer. This is where your ability to understand and communicate becomes crucial. What skills have you gained? Start with these, and add some of your own:

1. Independent learning skills: The ability to learn, and the ability to recognize opportunities to learn.

2. Research skills: The ability to find information and ideas, and the ability to critically distinguish between various sources of ideas.

3. Writing skills: The ability to structure your thoughts coherently and express yourself in ways that are appropriate to the occasion.

4. Reading Skills: The ability to understand language and systems of meaning, whether they occur in literal texts, or in other forms. Humanities students learn to read images, culture, and a host of other things, besides written texts.

5. Speaking skills: The ability to confidently and clearly express your ideas. The ability to convince someone of your arguments and persuade them of your point of view.

6. Critical thinking skills: The ability to tell better ideas from worse, the ability to test ideas by subjecting them to relevant criteria.

7. Electracy skills: The ability to read, navigate, and create the digital environment. (the term “electracy” comes from Gregory Ulmer).

8. Problem-solving skills: The ability to understand and express a problem that needs to be solved, and the knowledge of various methods of analysis that might be relevant to the problem.

9. Question formulation skills: The ability to recognize that all knowledge is really the answer to a question, and that truly understanding something means understanding the questions that are asked, and being able to refine those questions to produce better knowledge.

10. Interdisciplinary skills: The ability to work at the borders of traditional forms of knowledge, using the resources from more than one area to help define a problem or ask a question, and suggest approaches to addressing the problem or question.

11. Global understanding and cultural sensitivity: The ability to appreciate cultures and religious traditions outside of your own.

12. Historical understanding: The ability to see how and why things came to be as they are, and how they might be different.

13. Aesthetic understanding: The ability to recognize and produce visual, narrative, and musical structure, order, and appeal.

14. Perspectival understanding: The ability to understand how other people or groups think, and to value difference.

15. Adaptability: The ability to apply knowledge and skills to a wide variety of contexts.

16. Time and resource management skills: The ability to work under pressure and maximize resources to produce a desired outcome.

17. Linguistic skills: The ability to operate in more than one language.

18. Tact: No, not the ability to be discreet, but rather, the ability to know the right thing to do and to say at the right time. Aristotle called it “phronesis”, and it’s a sort of applied knowledge that comes through experience.

In a sense you have to do exactly what business programs think we should all do, which is to market yourself in a competitive world. And how do you market something? You know your product (yourself, in this case), and you know your market (what’s available out there, what the range of options are, who might be interested in someone with your skills). Some highly professionalized careers have very controlled access points (e.g., medicine, law), governed by training and qualification exams in their areas. A humanities degree might be the first step to one of those professional programs. That suggests more school, which would be necessary for many desirable careers today.

But if you just want to get a job after your undergrad degree, the best place you can go would be to your university’s career resource center. The people in that office should have concrete ideas about connecting your set of skills with current jobs.

5. What do people with humanities degrees do?

Lots of things. You will find successful humanities students in just about every area of human endeavor. Here’s a list of philosophy majors who have gone on to be famous in other fields, for instance. But lists like these only scratch the surface of where humanities grads have found themselves.

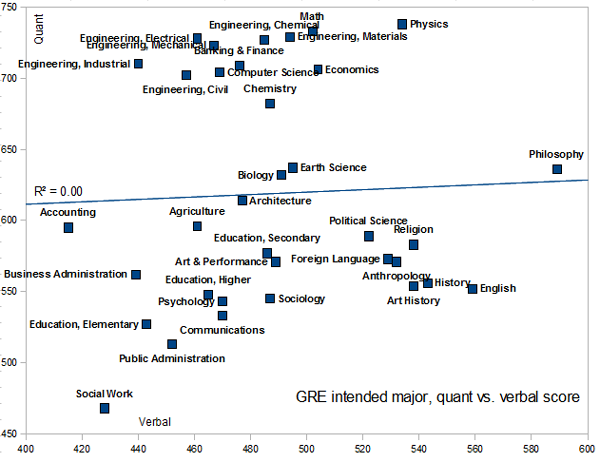

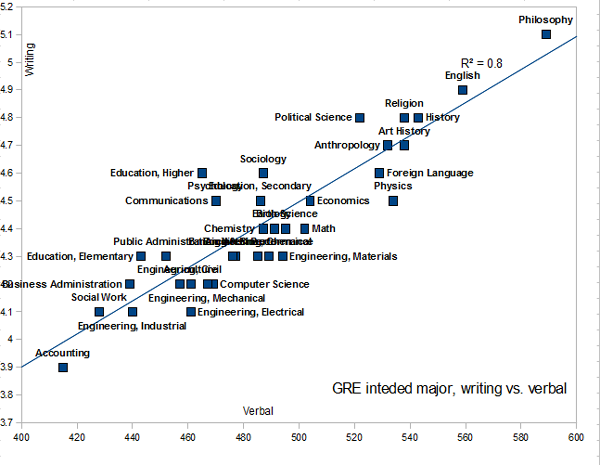

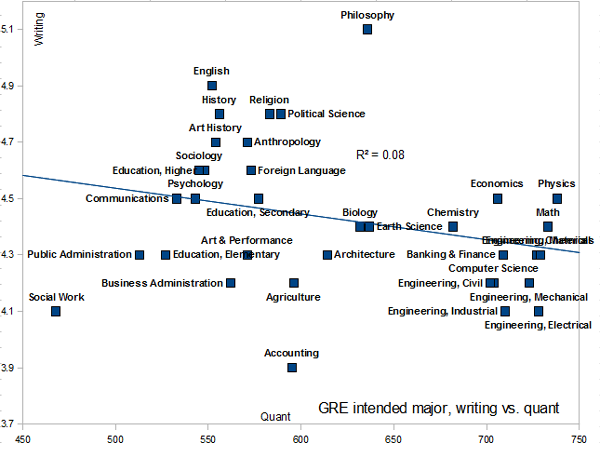

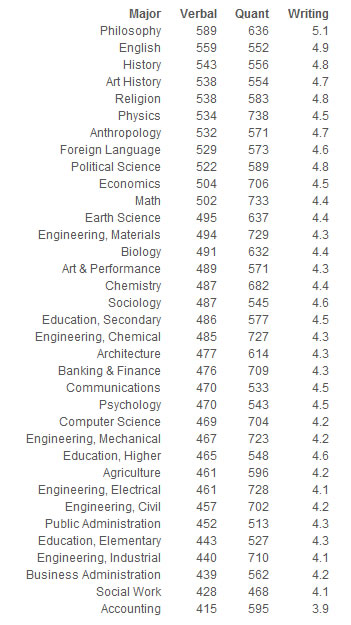

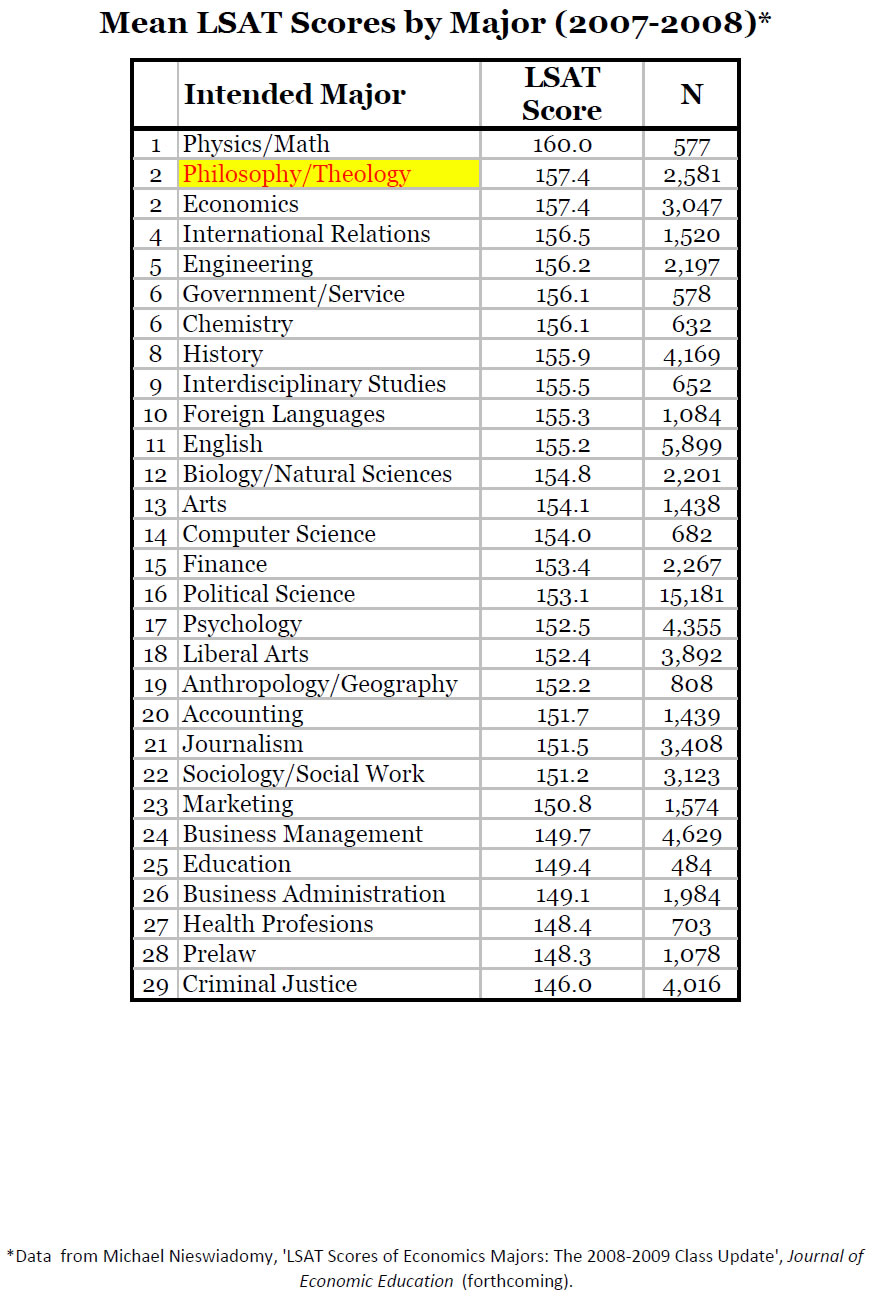

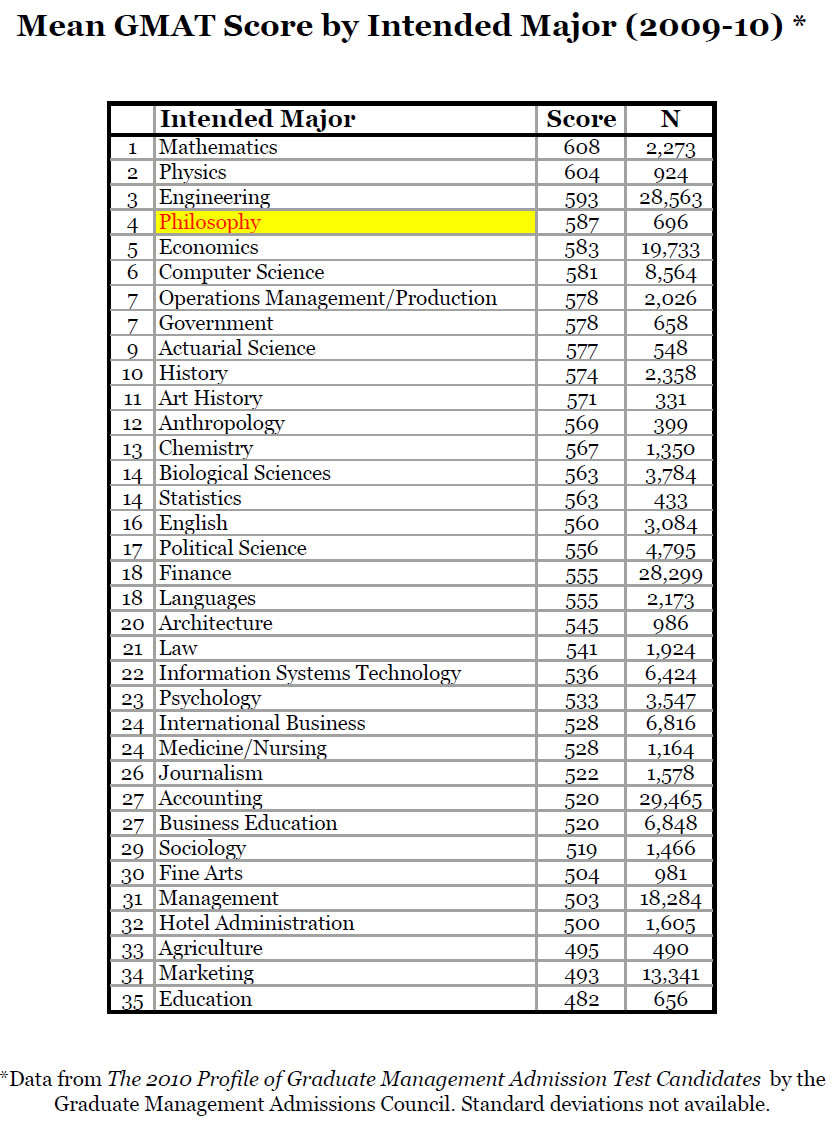

Don’t forget about graduate work as well. Many humanities majors go on for another degree, in some cases in the same area as their undergrad degree, in some cases in different areas. Humanities degrees may well be accepted by graduate programs outside of the humanities – it depends on the university and on the program. I have a page on graduate degrees in humanities, if you are interested. Some humanities majors also go on for post-grad professional degrees. A humanities degree in conjunction with law school, journalism school, seminary, or education college, for instance, can be an exciting combination. And, humanities degrees in general have proven to be excellent preparation for the GRE (Graduate Records Exam), the LSAT (Law School Admittance Exam), and other graduate requirements. Philosophy majors score extremely well on both qualitative and quantitative tests:

(Source: http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/gnxp/2010/12/verbal-vs-mathematical-aptitude-in-academics/)

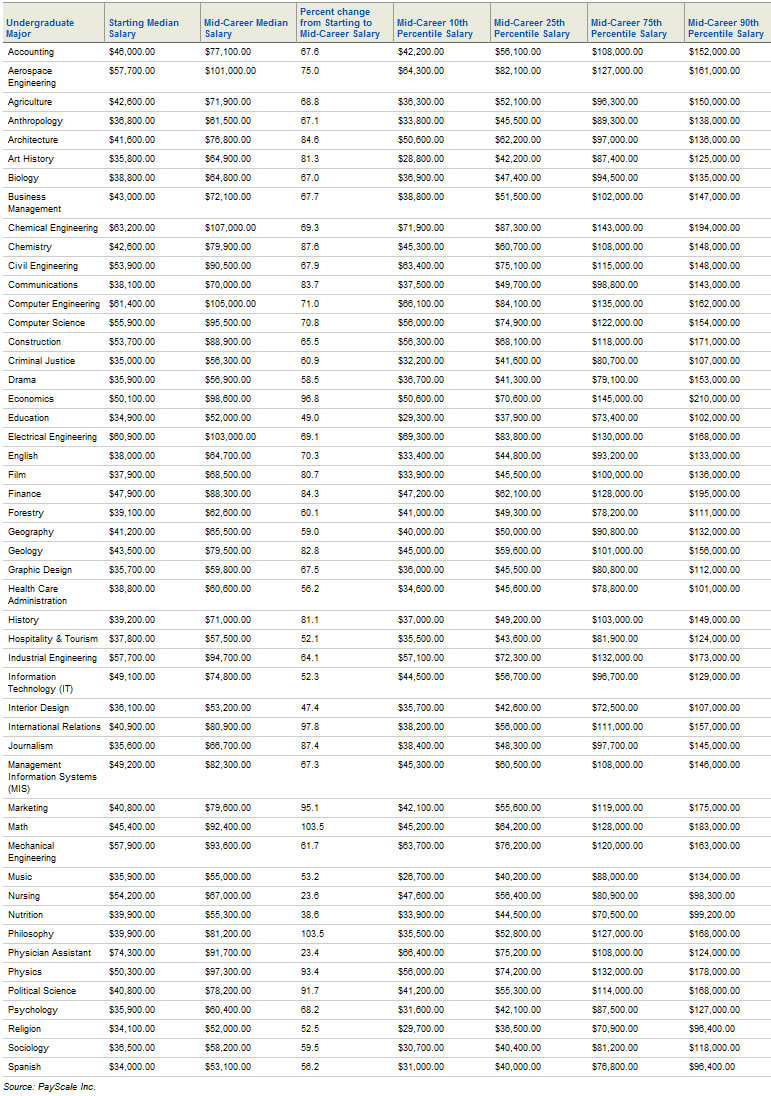

Want more stats? Here’s more to show that Philosophy, and the humanities in general, are great preparation for a range of graduate options. Philosophy graduates also start at a respectable salary, and have a higher rise in salary 10 years after matriculation. Thanks to Antony Aumann at Northern Michigan U. for these.

There are a lot of pressures today, to get into the right college, to choose the right degree, to succeed in an economy that has been difficult for many people. Humanities degrees are often misunderstood as uncompetitive and unproductive in that environment. The truth is, though, that in a difficult economic environment, there are no guarantees, and any program of education that offers one is not being straightforward with you. For most of us, there’s no magic bullet – do this, and you’re set for life, guaranteed. There’s a lot of luck, and chance, and things we have no control over.

But what we do have control over is ourselves. We can prepare ourselves to be flexible minds, open to new ideas. We can learn how it feels to do something because it might change the world, or it might at least make the world a better place for some few people. We can figure out how to actually learn from history, literature, art, philosophy, and religion, not so we are condemned to repeat it, but so that we might riff off of it.

And here’s another thing to keep in mind – the humanities today are not the humanities of the past. The image that many people have is of a pursuit that has no relation to practical human concerns. The fact is, humanities disciplines are involved in research projects of all sorts, with just about every discipline in the university. Philosophers work with scientists and engineers, historians work with medical professionals, creative writers work with digital media engineers. The fact is, every technical and scientific discipline, at some point or other, must also become a humanities discipline. Every scientific advance is an advance for humans, and is meaningful in our history, for the betterment of our lives. Every invention happens within the context of human meaning. Every business trades on human narratives and human desires as expressed through language and symbol. The humanities matter everywhere. Far from being marginal, they are central to all human life. They’re that important.

That’s why the humanities matter, and why a humanities education is a practical option. Talk to an advisor in your local humanities program – you might be surprised at what you find. It’s worth your time.

Links and Resources

Many of these links have extensive discussions of humanities careers, along with advice about how to prepare for life after university. An asterisk * denotes a particularly useful page.

- Philosophy is a Great Major

- The Truth About a Liberal Arts Education – Christendom College

- A very extensive list of public figures who did significant work in philosophy. Focuses on Canadians, but is not limited to them. Maintained by Raymont’s Lists, aka Paul Raymont.

- Career Information for Humanities Majors (Kansas State University)

- How Does Philosophy Relate To My Career? (Wilfrid Laurier University)

- *What Can I Do With A Major In…? (UNC Wilmington) – excellent ideas for many disciplines, including…

- UCF National Internship Directory

- Liberal Arts/History Jobs (Messiah College)

- Liberal Arts Job Search – Rice University

- Subject Center for Philosophical and Religious Studies, University of Leeds

- Will your philosophy degree get you a job? Studying philosophy as part of a non-academic career

- Jobs in Philosophy

- Cropper, Carol Marie, “Philosophers Find the Degree Pays Off in Life and in Work”

- Cole, Diane, “50 Ways to Improve Your Life: Learn Philosophy”

- McLeod, J. David. “The Deceptive Discourse” – value of a liberal arts education

- Rupp, Shannon, “Be Employable, Study Philosophy” (Salon, July 2013)

- Horgan, John, “Why Study Humanities? What I Tell Engineering Freshmen” (Scientific American, June 2013)

- Shepherd, Jessica, “I Think, Therefore I Earn” The Guardian, November 2007)

- Lalor, Brendan “Can I Get a Job With A Philosophy Degree?” ThereItIs.org

- Drolet, Daniel, “Philosophy’s Makeover” (University Affairs, November 2008)

- Scordo, Vincent, “Why Major in Philosophy?” (Scordo.com)

- Seidman, Dov, “Philosophy is Back in Business” (Business Week)

- Tenner, Edward, “Is Philosophy the Most Practical Major?” (The Atlantic)

- Greeley, Brendan, “Bernanke to Economists: More Philosophy, Please” (Business Week)

- Maddow, Rachel, “Interview at Ball State about the Humanities” December 2011

- A. G. Lafley, fmr CEO, Proctor and Gamble “A Liberal Education: Preparation for Career Success”

- National Employment Bulletins – subscription bulletins

- Philosophy: What Can It Do For You?

- So you have a degree in the humanities… (University of Calgary)

- *Planning Your Humanities Career – some excellent ideas and exercises on this site

- “Oh, The Humanities! Why STEM Shoudn’t Take Precedence Over the Arts”