From Dec. 3 2016

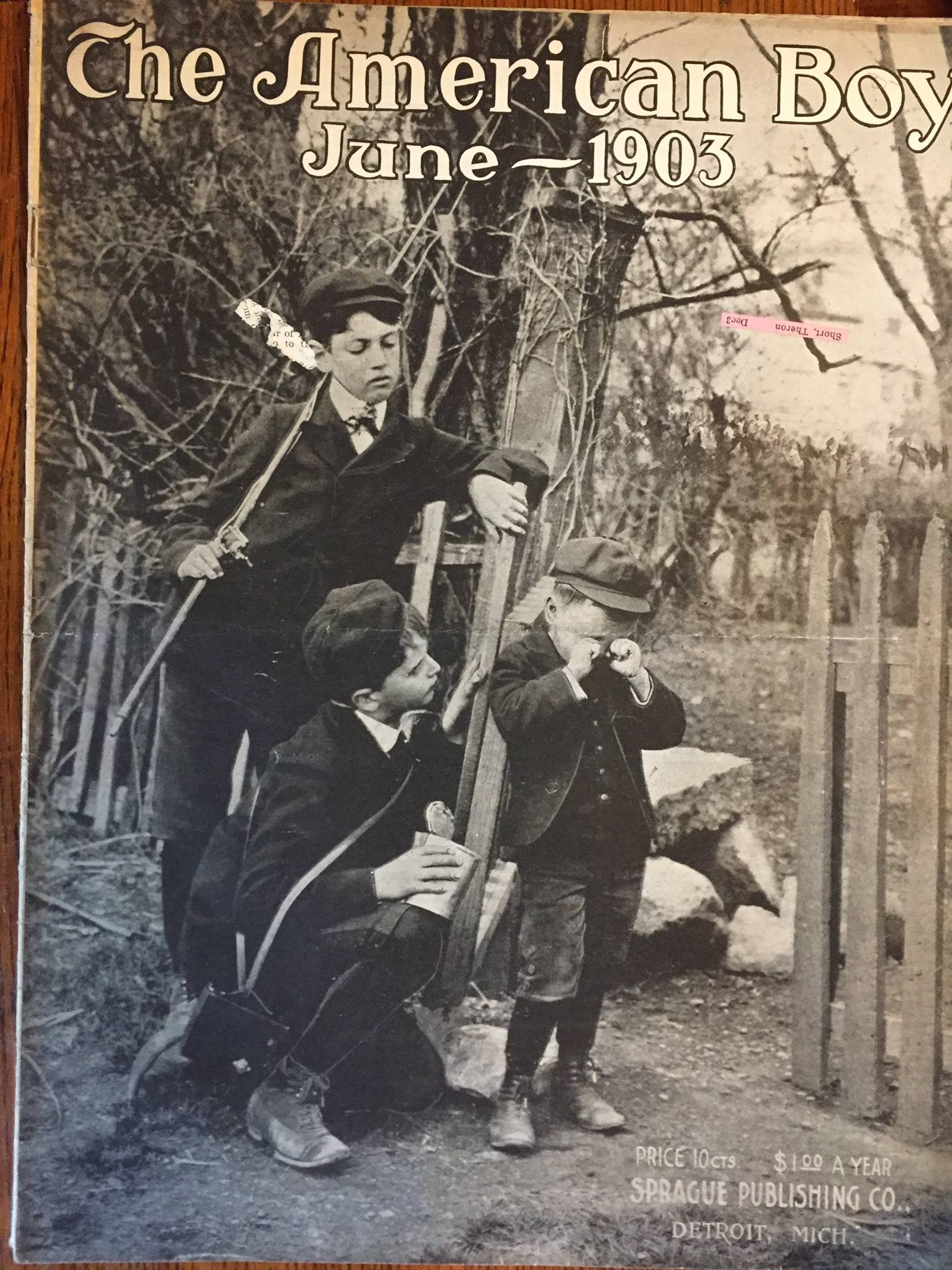

I was reading through my June 1903 copy of The American Boy, as one does, and came across this little racist nugget in an article on lacrosse:

“It is characteristic of the white boy that he should borrow a game from the Indian, learn it thoroughly and then beat the original player by sheer force of superior head work.”

Superior head work. I assume that doesn’t refer to head-butting the opposing players, but it might. I’d like to think it does. And, so that we don’t think that it’s all about race, the end of the article throws some artfully phrased shade at the Brits:

“Quick, snappy work is essential to success in lacrosse. It is a game that the American boy should excel in, for certainly slowness is not one of his failings. Were it not for the fact that the much talked about sluggishness of the British nature has been most singularly conspicuous by its absence whenever British athletes have taken the field against our boys, it would be safe to predict that the visiting team from Oxford and Cambridge will be soundly beaten in the lacrosse games.”

And so I thought to myself, those were the days when the racism was right out in the open, and the nationalism was at its irrational finest. The other thing that struck me, though, was that in this magazine, the top-selling one of its day to boys, there is this story constructed about racial and national superiority. Nothing new about that, of course, but it strikes me that all this talk is about character and nature. Everything springs from the innate and essential nature, rooted in race, nurtured by nation.

It’s aspirational. If you’re not like that, you want to be. And this is, perhaps, the threat of diversity to those who want to hold stories like this. In 1903, it was obvious that there was one thing for the white American male to aspire to. One template. You either bought that story, or you didn’t fit and never would. Diversity is not just a threat to a system that bought that aspirational story completely, it is an existential threat, because it says that there are multiple ways to be great.

There is an irony here – along with this homogenized story, we have faith in a market, which in order to work requires diversity. You don’t get innovation unless there is difference, unless people have things to choose between. On the face of it, the greatest diversity would come from the widest range of sources, which would imply national, cultural, religious diversity. How do these things add up?

As it turns out, it’s not much of a stretch. In classical economics (by which I mean 19th century theory, especially from John Stuart Mill), we can’t look inside someone to see their character at all. All we know is their action, in the context of everyone else’s action. That’s what a market is. So Mill is an early and ardent proponent of anti-slavery, gender equality (no doubt he got some of this from Harriet Taylor, his wife), and all sorts of other things. Why? Because there was no intrinsic hierarchy of character for him. All we had was the action we could all see. If people made different choices, it wasn’t because one person was “good” and the other “bad”, but because they had different opportunities and constraints, that is, external formative factors on their actions.

How do we get from there to someone believing both that there are internal characteristics, and they are unequally distributed, and white male Christians are by definition the best, and on the other hand believing in the market, which gives no place to those internal differences, if they exist at all, and focuses only on external action? One of these beliefs would seem to undermine the other.

One answer would be the one we see in the quote above about lacrosse. The Indians invented it, but the white boy perfects it because he’s smarter. That’s the “smartest person in the room” theory we hear so often from Wall Street traders – they’re wealthy because they are smarter than everyone else. They see the opportunities and take them. Of course, when someone loses money, that is not then taken as an indication of not being smart. And, the fact that most of these traders come from a small number of families, schools, locations, etc., is also not given any weight. Any success is about intrinsic smartness.

Trump gives us another account of how these things get put together, which is narratively. Is Trump successful as a business person? There’s plenty of reason to think that he isn’t. He has a string of bankruptcies, he doesn’t release his taxes (which would tell us what he is actually worth), he regularly cheats his suppliers and workers. But it is an article of faith that he is successful. It reminds me of George Lakoff’s argument, that the Republican story is about the firm father figure. Trump fits that. I don’t know how many times I’ve heard a Trump supporter say that everything will now be good, because he’s in control. Is there any idea of a plan? No. Dad will fix it. We trust dad. For white Americans, Obama was never dad, even though as a literal father figure he was far better than Trump. Hillary Clinton could never be dad. People wanted a dad.

What does this have to do with the seeming conflict between internal character and external market action? Simply that when you put a powerful narrative in place, there is a link between character and action. Trump is not great because of his internal character – pretty much everyone, even his supporters, recognize that his character is horrible. But he occupies a place in a narrative. He is dad. In a complex world, we can hand things over to dad and he’ll take care of us. He’s the smartest one around, he’ll stick up for his kids. His character comes from his position in a longstanding narrative.

And as for markets – that’s easy too. He’s dad, and he’s a businessman. He’s a billionaire, and he’s put lots of other very rich people in places of power already. What could be better? These are our moral betters, because they are the Smartest People In The Room. How do we know that? Because they are rich. No other reason. A bank account is a scorecard for life, and they are winning. They too occupy places in a narrative. Their character is their action, and look at what they’ve done – they are rich. They must be right.

Those who tell everyone “just given them a chance” are really saying, just become kids again. Just give it all over to Daddy and his friends. It’s a big scary world, but they’ll look after us. And by “us”, we mean us real Americans, not those black kids or those gay kids or any of the others. The real American Boy. All the things that scare us, all those monsters out there, he’ll make them go away. How will he do that? Doesn’t matter, he will. He doesn’t need to tell us his plans. We’re the kids, and we’re safe now.

We need a better story, because this false fairy tale has captured far too many minds.